Last Friday, instead of making straight for the Red Line to head home after work, as has been my habit the vast majority of evenings, I hung around in the Loop for a bit, scoping out potential dinner spots and deciding against the crowdedest and most tourist-friendly spots. I ended up at the Grillroom, just across the street from the CIBC Theatre, which was a touch more upscale than I would have preferred, as I was carrying my work bag and wearing a bulky hoodie against the November chill, but the soothing ambience and professionally accommodating waitstaff were nice, the salmon was good if overpriced, and the distance from my next stop couldn’t be improved on.

I’d noticed the Broadway in Chicago banners on State Street advertising Boop! The Musical for several weeks on my brief walks to get lunch or catch the L, but I didn’t actually look up the show until I noticed one day that the banners had changed to advertise a winter festival. On a whim, I bought a balcony ticket — what the hell, I’ve always been interested in old animation, and a night at the theater is an exceedingly rare treat in my quiet life — and then set several reminders, since the gravitational well of ingrained habit getting me back to my apartment before I remembered the plans I’d made weeks ago is always a concern.

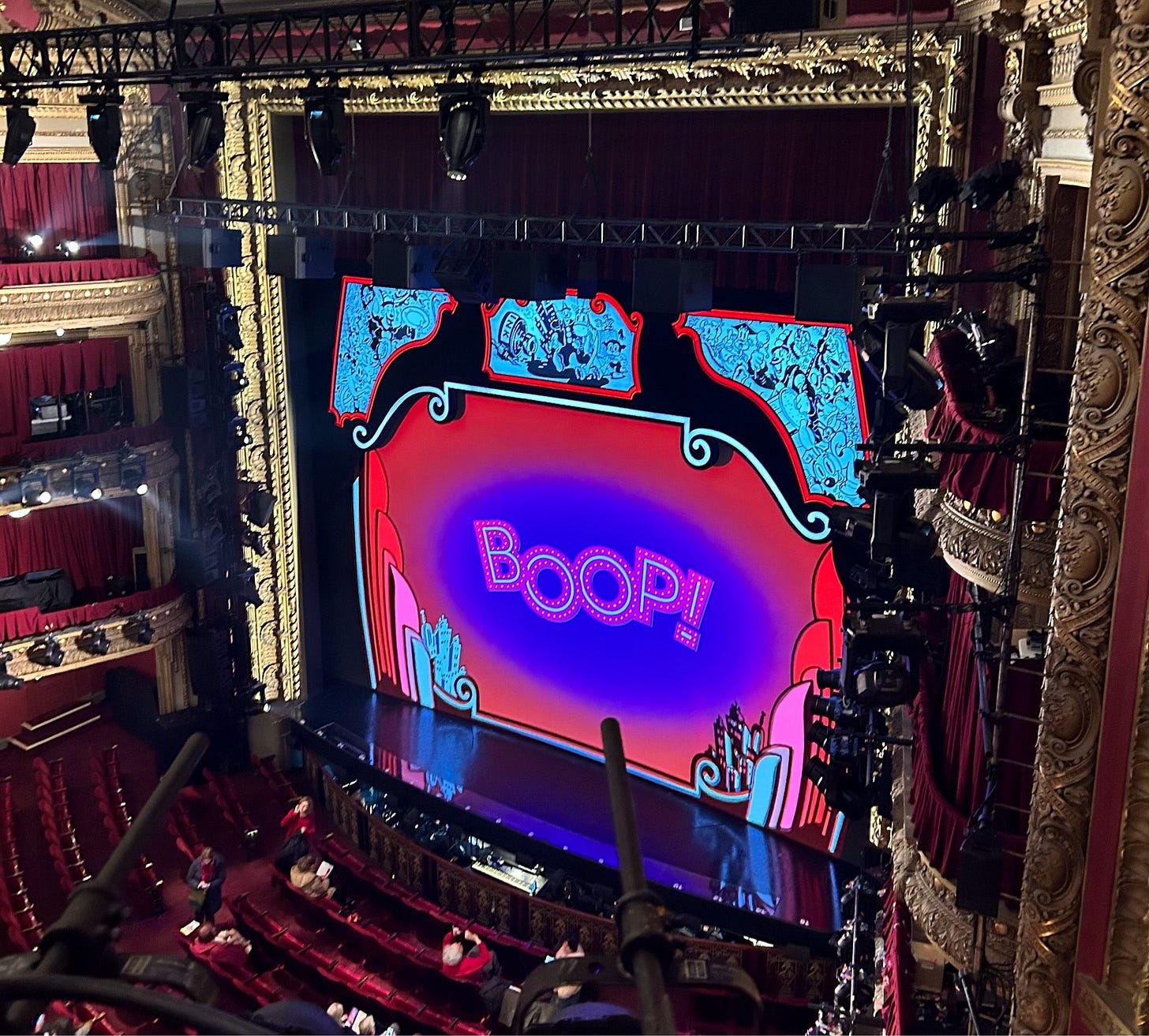

But no, I paid my dinner bill a half hour before show time and went down to the crosswalk to cross the street. (“Enjoy the show,” said the waiter to the table next to mine, who had been more forthcoming about their plans for the evening.) The CIBC Theatre was built in 1906 (it was called the Majestic then; the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce bought the naming rights in 2017, the most recent of a series of banks to do so), and the grand Beaux-Arts auditorium has been well-preserved slash restored, with rows upon rows of filigree that gives you something to look at long before the show begins.

And the pre-show set dressing really got my hopes up.

The decorative cornices on the proscenium screen bore black-and-white pen illustrations of other Fleischer cartoon characters, including Koko the Clown and the anthropomorphic dog Bimbo, with the central panel even referencing the 1918 Out of the Inkwell series that put Max Fleischer on the map of animation history. Betty Boop herself is absent from the drawings, naturally; the star of the show must be preserved for the stage. But I took the drawings as an encouraging sign that there were some real animation nerds involved with the production, even if it was only the designers.

My interest in the Betty Boop cartoons doesn’t extend past the censorship imposed in 1934 by the Hays Code (and honestly the two shorts featuring Cab Calloway songs are the only ones I really know well), so I was unfamiliar with the character Grampy, Betty’s eccentric inventor grandfather (?), who debuted in 1935. But he, and her dog Pudgy (debut September 1934), are the only other Fleischer characters who made it into the show.

Thematically, as it turns out, this is appropriate: Koko and Bimbo starred in their own cartoons — although Betty’s debut was as Bimbo’s dog-eared girlfriend, a factoid responsible for a couple of laugh lines in the stage show — but Grampy and Pudgy are very much Betty’s supporting cast, and in the (sigh) lore established by Bob Martin’s book, the cartoon world of Betty Boop hinges upon the fact that it is her world: if she’s not in it, having (or filming) the black-and-white cartoon adventures that make up the Betty Boop corpus, it will disappear.

Which is by way of stakes-setting because the plot of the show is that Betty Boop uses one of Grampy’s inventions to visit the Real World — capitalized because the real world as depicted in a Broadway musical is different enough from the actual real world in which I’m typing this (what with everyone bursting into song every ten minutes, constantly making big declarative statements about their emotions, and neatly resolving every problem they encounter within two hours) that it has to be considered as much a fantasyland as the very inventive black-and-white world that the opening number depicts as Betty’s home.

Boop! is, in fact, a companion piece to this summer’s Barbie movie, which I never got around to seeing because I am bad at keeping abreast of culture. But it’s my understanding that the basic plot of “equivocal 20th-century entertainment icon of fill-in-the-blank femininity visits the real world, vaguely disrupts it, and has her own iconicity endlessly reiterated back to her because that’s just good brand management” is shared between the two vehicles; if producer-director-choreographer Jerry Mitchell’s vision of Betty Boop as the ideal woman ends up being less complex than Greta Gerwig’s take on Mattel’s plastic tabula rasa, that may be due as much to differences in the state of the medium in 2023 as anything else: a family-friendly pop-culture musical stage show that has to please investors before audiences doesn’t allow for nearly as much subtlety or cultural critique as even a toy tie-in movie.

In fact, the movie it reminded me of most strongly was The Lego Movie, as I noted on Bluesky:

at intermission, what it’s reminding me of most strongly is a lord/miller movie. pomo pop-cult mèlange overinsisting on the spiritual value of the core intellectual property is probably the only way something like this gets staged, but the technicians involved do astonishing work

Swap out action setpieces for musical numbers, and it’s a pretty solid entry in any post-Marvel excuse for hanging a narrative around a piece of pop culture in order to drive consumer interest: if the show is a success when it moves to New York, Betties in black wigs and little red dresses will undoubtedly join the Chewbaccas, Iron Mans, and shirtless Winnie-the-Poohs in Times Square. A trio not chosen at random: members of the ensemble in these costumes, playing Times Square tourist-bait, back up Broadway legend Faith Prince in her showcase number as Grampy’s elderly love interest; bizarrely enough, given the historical origins and blazingly obvious semiotics of the Betty Boop character, this number is just about the only time the show approaches sexiness.

Don’t get me wrong: Jasmine Amy Rogers in the central role is gorgeous, hilarious, and phenomenally talented, a genuine rising star who makes it difficult to notice anything else when she’s on stage. But Martin’s book is so obviously written with young girls in mind that there’s one in the show, America’s Got Talent runner-up Angelica Hale playing a spunky New York pre-teen who is obsessed with the cartoon character Betty Boop for reasons that the script strains to make credible and mostly boil down to “she’s iconic.” Why she’s iconic — why, for example, she got painted on the noses of fighter planes in World War II, or why her most popular merchandise all has her in skirts short enough to show off a garter — is never broached, let alone synthesized.

Unlike Jessica Rabbit (not bad, just drawn that way), Betty is presented by Boop! as a childlike naif whose nearest aproach to adult sexuality before entering the Real World was being chased by men for unspecified reasons before she clobbered them over the head with the nearest available implement. And aside from a storming musical number or two, she never really advances past that naivety in the Real World either, despite entering into a trans-dimensional romance with a New Yorker who loves jazz. All of which is perfectly appropriate for a musical aimed as much at children as at the parents buying the tickets; but despite Martin’s protestations, I’m skeptical that there are really a lot of Boop-heads to be found in a generation with no first-hand experience of the twentieth century.

But speaking of the storming musical numbers. The music is by David Foster, best known for adult-contemporary schlockbuster ballads of the 1980s, and there’s an oddly archaic 1980s quality to the entire show, failing to live up to either the hot jazz of the 20s and 30s that Betty originated in or any remotely contemporary sounds. Not, indeed, that I was hoping for a trap-reggaeton-hyperpop score, especially as filtered through David fucking Foster, but even by Broadway standards the music is old-fashioned. Not, of course, old-fashioned enough, by my lights — but remember, I’m the guy who loved loved loved Shuffle Along; and Foster even admitted in interviews that he tried to follow the lead of the 1930s cartoons but “my ear is just not very attuned to that sound.”

So the closest we get to jazz is the cod-gospel of “Where I Wanna Be”, the showstopping Act I closer, when Betty finally appears in the iconic red dress from the posters. The rest of the songs are generally fine, if bland and relatively generic — since it’s in previews, there are a few more numbers than will probably end up in the final show, including two back-to-back songs about how awesome Betty Boop is — but I will admit that the closing refrain has been stuck in my head for the past five days; Foster may be incapable of pastiching 30s jazz, but a big sweeping generalized love song is his bread and butter. Although the sentiment of the chorus — “Why look around the corner when it’s all right here?” — doesn’t reinforce any of the themes of the foregoing several hours, and indeed encourages a kind of smug, quiescent passivity that is exactly the opposite of what the political moment is calling for. But that’s the kind of overthinking that having something stuck in your head will get you.

There was an unexpected applause break in the show when I saw it: after Betty, disgusted by the venal politician who has been attempting to use her popularity to bolster his campaign for New York mayor (the show sells New York really hard, by the way, which feels especially weird in Chicago previews), rattles off a list of trite observations about the Real World’s income inequality, the audience whooped leftishly, throwing off the performers and almost stepping on a punchline about Jeff Bezos. That disconnect between what the show ultimately really is (mass entertainment with no real convictions beyond “you go girl” and “love conquers all”) and what even audiences that will pay Broadway prices for an out-of-town preview are hungry for in 2023 is, more than anything, what makes me uncertain about the future of Boop!

Because ultimately I had a great time. The technical wizardry of the production kept me rapt all night, with inventive use of staging, illusions, projections, and puppetry (Pudgy, marionetted by Phillip Huber, steals the show from everyone but Prince and Rogers), and the book is witty enough to work on its merits despite my reservations about the larger themes and meaning. And whatever his faults as a lowest-common-denominator producer, Jerry Mitchell’s choreography is a lot of fun to watch; the ensemble was brilliant, and the show is a rousing spectacle even on a relatively lean budget.

And as for the best thing about it:

Casting a Black woman in the central role does unexpected justice to the ambiguously raced Betty of the Fleischer cartoons, which were produced in an era when anything tinged with jazz raciness was understood to be tainted by association with the Negro. (That was part of what made the Fleischer cartoons so much more urban and adult than the pastoral, whitebread Disney.) In looks and voice she was based on white cabaret singer Helen Kane, but when Kane tried to sue the Fleischers and voice actor May Questel for ripping off her signature voice, they pointed to an earlier Black singer who had employed a similar sexy-baby voice, and got the courts to agree that Kane’s style wasn’t original enough to be protected. Of course, Baby Esther, that Black singer, never got her due either; she had disappeared by the time of the lawsuit, and the test recordings allegedly produced in court have been lost. So, by a circuitous path, it is a kind of vindication for the Texas-born Rogers to be the woman embodying the cartoon who stole the bread from Helen Kane’s boop-a-dooping mouth.

She doesn’t attempt to replicate Questel’s speaking voice, or Kane’s singing: her voice is rich and powerful, not squeaky and cute, and she uses it in full. And the “woiking goil” Brooklyn accent which was, in its day, a marker of Betty’s sexual availability only occasionally surfaces, generally when Martin’s script calls for it as a laugh line. Her Betty is a full person, not a cartoon avatar; which is a little odd, because part of the tension of the show is the juxtaposition of a cartoon avatar against living, breathing space. It’s not a tension that is ever wholly resolved (or capable of it, I would argue; the sheer unreality of the premise makes thinking too hard about it unadvisable), but Rogers excels at living in the center of it, with big cartoon reactions that are justified by the big reactions required by the stage. Even though the premise is preposterous, she finds a way to ground even the unlikeliest emotions, so you end up rooting for Betty no matter how dumb the rest of the story around her gets.

And it can get pretty dumb: while the A plot romance is perfectly fine, if predictable from beat one, the B (Grampy reconnecting with the young woman in the Real World who once fell for him, only she’s grown old to match him because cartoon characters don’t age) and C (painfully broad satire on corrupt New York politics, as told to children with no sense of scale or history) storylines take up time that the audience would rather spend with Betty. Or in her gray-toned original world, if you’re me; but the revelation that it only exists because she does is, while existentially intriguing, kind of deflating for anyone hoping for more genuinely cartoony antics.

I genuinely hope the show does well, if only for Rogers’ sake; I was glad to notice more Black patrons at the theater than I might have expected (the whiteness of the Shuffle Along audience when I saw it in New York was dispiriting), and the show’s Instagram posts are full of commenters rejoicing over Rogers’ casting, with an awareness of the character’s racialized past that surprised me. And while I’m as exhausted as anyone with the stale recycling of old pop-culture iconography as the only way new media ever gets made, my fondness for old black-and-white animation and the complicated weirdness of the past makes it hard to root against anything with even as tenuous a connection to that past as this production has.

Oh and hi, by the way. I’m dusting off this old newsletter (and returning, grumbling, to Substack since Twitter killed Revue and Mailchimp is killing Tinyletter) because I want to try to write in public again. I can’t make any promises that it will become a regular thing, especially since that gravitational well of ingrained habit is all against it. But I miss telling people what I’m thinking about, and I miss having thoughts worth telling people about.

Thanks to Erik for encouraging me to write this up. I’m no theater critic, and I don’t think I’m breaking any embargo by writing about the show before the New York opening. In fact, I hope that when it does open there it’s a better show.

See you around.